Damascus steel represents a remarkable synthesis of historical craftsmanship and modern metallurgical engineering, holding a revered position in the realm of high-performance cutlery. Esteemed for its distinctive layered patterns, this material is produced by forging multiple types of steel together, a technique that yields a blade with a superior balance of hardness, flexibility, and edge retention. The enduring demand for these knives in both professional and domestic kitchens highlights their continued relevance, not only as exceptional cutting tools but also as objects of significant aesthetic value. This combination of superior function and unique beauty makes the material a benchmark for quality in the culinary world.

Navigating the contemporary market to find a genuine, high-quality blade can be a formidable task, given the wide variance in manufacturing processes, materials, and overall craftsmanship. An informed purchasing decision requires an understanding of core steel types, layering techniques, and the subtle indicators of quality that separate a premium tool from a mere imitation. This comprehensive guide serves to demystify this complex landscape, offering critical analysis and detailed reviews to help you identify the best damascus steel knives for your specific needs. By focusing on essential performance metrics and construction integrity, we provide the necessary insights to ensure your investment is both lasting and rewarding.

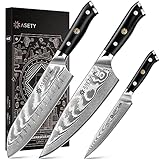

We will discuss the best damascus steel knives further down, but for now, consider checking out these related items on Amazon:

Last update on 2025-07-20 / Affiliate links / #ad / Images from Amazon Product Advertising API

An Analytical Overview of Damascus Steel Knives

The market for Damascus steel knives has seen a significant surge in popularity, evolving from a niche for collectors and professional chefs to a mainstream desire for high-performance, aesthetically pleasing kitchen tools. This trend is largely driven by the visual appeal of the distinctive, wavy patterns, which makes these knives a centerpiece in modern kitchens. The primary trend is one of accessibility; while traditionally a hallmark of expensive, artisan craftsmanship, modern manufacturing has enabled a wider range of products at various price points. This has democratized ownership, but it has also created a more complex market for consumers to navigate, with quality and authenticity varying dramatically between manufacturers. The allure of Damascus steel is no longer just about its historical mystique but about its status as a piece of functional art.

From a performance standpoint, the benefits of a well-made Damascus knife are rooted in its composite construction. The blade is typically made by forge-welding multiple layers of steel around a central cutting core. This core is usually a very hard, high-carbon steel, such as VG-10 or AUS-10, which can be heat-treated to a Rockwell hardness of 60-62 HRC. This is substantially harder than a typical German steel knife (around 57 HRC), allowing for a more acute edge angle and superior edge retention. The softer, often stainless, outer layers of “Damascus” cladding serve a dual purpose: they protect the brittle, high-carbon core from chipping and provide a degree of stain resistance, creating a blade that balances exceptional sharpness with practical durability.

Despite their advantages, Damascus steel knives present distinct challenges for consumers. The most significant issue is market transparency and authenticity. Many lower-cost “Damascus” knives feature a pattern that is merely laser-etched or acid-etched onto the surface of a monolithic steel blade, offering no structural benefit and misleading the buyer. Distinguishing genuine layered steel from these cosmetic imitations requires knowledge and a keen eye. Furthermore, the high-carbon core that provides excellent cutting performance is more susceptible to corrosion and rust than standard stainless steel. This necessitates a more rigorous maintenance routine, including immediate hand-washing and drying after each use, which can be a drawback for those accustomed to low-maintenance cutlery. Navigating this market to find the best damascus steel knives requires a discerning eye and an understanding of the materials used.

In conclusion, the Damascus steel knife category represents a fascinating intersection of metallurgy, artistry, and performance. The current landscape is characterized by a blend of ancient tradition and modern innovation, offering consumers a product that is both a superior cutting tool and a statement piece. While challenges related to authenticity and maintenance persist, the fundamental value proposition remains strong. The ongoing innovation in pattern complexity and the use of advanced powdered steels suggest that the future of Damascus is bright. For the discerning user willing to invest in both the product and its proper care, a Damascus steel knife offers an unparalleled combination of enduring sharpness, resilience, and timeless beauty.

Best Damascus Steel Knives – Reviews

Shun Classic Chef’s Knife (8-inch)

This knife is constructed with a proprietary VG-MAX cutting core, a steel formulation enriched with carbon, chromium, cobalt, and tungsten, which is heat-treated to a Rockwell hardness of approximately 60-61 HRC. The core is clad on each side with 34 layers of stainless Damascus steel, resulting in a 69-layer composite blade. This layering not only provides a distinctive aesthetic but also supports and protects the harder central core. The blade geometry features a double-bevel edge ground to a 16-degree angle per side, which is more acute than typical Western knives. The handle is made of ebony-finished Pakkawood, a resin-infused hardwood composite, and is engineered with a D-shaped profile for a secure grip, primarily optimized for right-handed users.

In terms of performance, the VG-MAX core provides a well-balanced combination of sustained edge retention, high corrosion resistance, and relative ease of sharpening when compared to more advanced powder metallurgy steels. The acute 16-degree edge angle facilitates precise, low-effort cuts. The Damascus cladding creates microscopic air pockets on the blade’s surface, which can offer a marginal reduction in friction and aid in food release. The knife’s value is derived from its consistent manufacturing quality, brand reputation, and versatile performance. It serves as a benchmark for the premium kitchen cutlery market, representing a reliable and functional investment for both dedicated home cooks and professional chefs.

Miyabi Birchwood SG2 Chef’s Knife (8-inch)

The core of this knife is forged from Micro-Carbide SG2 powder steel, a material known for its fine grain structure and high alloy content, achieving a Rockwell hardness of approximately 63 HRC. This core is protected by 50 layers of stainless steel on each side, culminating in a 101-layer blade with a distinct floral Damascus pattern. The blade undergoes a three-step Honbazuke honing process, resulting in a surgically sharp edge with an angle between 9.5 and 12 degrees per side. The handle is crafted from Karelian (Masur) Birch, a highly figured and durable wood, shaped into a traditional Japanese D-profile and accented with a mosaic pin and steel end cap.

The SG2 steel core delivers exceptional and prolonged edge retention, significantly outperforming more common steels like VG-10, although it necessitates more advanced sharpening equipment and techniques to maintain its fine edge. The extremely acute blade angle provides superior cutting precision, minimizing cellular damage to ingredients. While aesthetically striking, the Karelian Birch handle requires more diligent maintenance than synthetic alternatives to preserve its integrity. The Miyabi Birchwood is positioned as a luxury culinary instrument; its high cost is a direct reflection of its superior material composition, meticulous craftsmanship, and elite cutting performance, making it a justifiable acquisition for enthusiasts who demand the highest standards.

Kramer by Zwilling Euroline Damascus Chef’s Knife (8-inch)

This knife features a core of SG2 Micro-Carbide powder steel, hardened to a Rockwell rating of 63 HRC for superior edge-holding capabilities. It is clad with 50 layers of steel per side, creating a 101-layer blade distinguished by a bold chevron Damascus pattern designed by master bladesmith Bob Kramer. A key design feature is the wide blade profile, which provides ample knuckle clearance on a cutting board and facilitates the scooping and transferring of chopped foods. The handle is constructed from polished black Micarta, a highly durable linen and resin composite, and is affixed with a full tang and three rivets, including a signature Kramer mosaic pin.

The knife’s performance is a synthesis of Japanese material science and Western ergonomic design. The SG2 core ensures long-lasting sharpness, while the wide, robust blade shape provides the practical utility favored in Western kitchens. The rounded spine and bolster are engineered for comfort in a professional pinch grip, reducing fatigue during extended use. The Micarta handle is dimensionally stable and impervious to moisture, offering a secure grip that contrasts with the maintenance requirements of natural wood. The value of the Kramer Euroline lies in this unique combination of a master-designed functional form with high-performance materials, offering a premium tool for users who seek the edge performance of Japanese cutlery within a familiar Western-style framework.

Yoshihiro VG-10 Hammered Damascus Gyuto (8.25-inch)

This Gyuto is centered around a VG-10 high-carbon stainless steel core, a material widely regarded for its reliable performance and hardened to a Rockwell C scale of approximately 60. The core is clad with 16 layers of Damascus steel on each side and features a hammered finish, known as tsuchime. This texturing creates small, irregular divots across the upper portion of the blade. The blade profile is that of a traditional Japanese Gyuto, slightly flatter than a Western chef’s knife with a more acute tip for precision work. It is fitted with a traditional octagonal Wa-handle made from Shitan Rosewood, which is lightweight and provides a secure, tactile grip.

The performance of the VG-10 core offers a highly effective balance of sharpness, toughness, and ease of sharpening, positioning it as a dependable workhorse steel. The combination of the Damascus pattern and the tsuchime finish creates air pockets between the blade and the food, which significantly reduces friction and minimizes sticking, particularly with starchy or wet vegetables. The lightweight, octagonal handle promotes a nimble, forward-balanced feel, which is advantageous for the push-and-pull cutting motions common in Japanese culinary techniques. In terms of value, this Yoshihiro knife delivers authentic Japanese design and functional enhancements at a competitive price point, making it an excellent option for users seeking traditional craftsmanship and high performance without the cost associated with exotic powder steels.

Dalstrong Shogun Series X Chef’s Knife (8-inch)

The construction of this knife is based on a Japanese AUS-10V high-carbon steel cutting core, cryogenically treated and hardened to over 62 HRC. The blade is clad with 66 layers of high-carbon stainless steel, resulting in a visually intricate pattern Dalstrong markets as “Tsunami Rose.” The edge is sharpened to an acute angle of 8-12 degrees per side using the traditional three-step Honbazuke method. The handle is made from G10 Garolite, a military-grade fiberglass and epoxy composite, ergonomically shaped for ambidextrous use and affixed with a full tang, a decorative mosaic pin, and an engraved end cap.

From a performance standpoint, the AUS-10V steel core exhibits excellent edge retention and durability that is highly competitive with, and in some metrics exceeds, that of VG-10 steel. The aggressive edge geometry provides exceptional sharpness directly out of the box, suitable for fine slicing tasks. A significant feature is the G10 handle, which offers superior durability, complete resistance to moisture and heat, and a non-slip texture, making it ideal for rigorous use in both home and commercial kitchens. The primary value proposition of the Dalstrong Shogun Series is its high specification-to-cost ratio. It provides materials and performance attributes, such as the high-hardness core and G10 handle, that are typically associated with higher-priced cutlery, presenting a compelling choice for consumers focused on maximizing technical features per dollar spent.

The Practical and Economic Case for Damascus Steel Knives

The primary practical driver behind the need for high-quality Damascus steel knives is rooted in their superior performance, which results from their unique composite construction. Modern Damascus, or pattern-welded steel, is created by forge-welding multiple layers of different steel alloys. In the best examples, this involves laminating softer, more resilient steel layers around a very hard, high-carbon steel core. This sophisticated structure provides a distinct advantage: the hard core allows for an exceptionally sharp, long-lasting cutting edge with superior edge retention, while the outer layers add toughness, shock absorption, and corrosion resistance. This makes the knife not only a high-performer for precise tasks but also more durable and resilient to the rigors of daily use compared to a monosteel blade.

Beyond pure performance, practical need is also driven by the aesthetic and ergonomic experience of using a finely crafted tool. The intricate, unique patterns on each Damascus blade are not merely decorative; they are a visual representation of the complex forging process and the skill of the bladesmith. This elevates the tool from a simple utensil to a piece of functional art, fostering a greater pride of ownership and a more engaging user experience. For professionals like chefs and serious home cooks, using a tool that is both perfectly balanced and visually stunning can enhance the joy and precision of their craft. This desire for a superior tool that performs exceptionally and provides aesthetic satisfaction is a significant practical factor in the decision to purchase a Damascus knife.

From an economic perspective, the acquisition of a premium Damascus steel knife is often viewed as a long-term investment rather than a simple purchase. While the initial capital outlay is significantly higher than for mass-produced knives, their longevity and durability present a compelling value proposition. A well-made Damascus knife, with proper care, can last a lifetime and even be passed down as an heirloom, negating the need to repeatedly purchase and replace lesser-quality knives. This lowers the total cost of ownership over time. Furthermore, knives from reputable makers or forges often retain their value well, and in some cases, can appreciate within collector circles, making them a tangible asset.

In summary, the need for the best Damascus steel knives is a synthesis of practical demands and sound economic reasoning. Consumers are driven by a requirement for elite cutting performance—unmatched sharpness and edge retention—combined with the enhanced durability that the laminated construction provides. This practical need is complemented by the economic logic of investing in a long-lasting, high-quality tool that holds its value and provides a superior user experience. The demand stems from a discerning clientele, including professionals and enthusiasts, who understand that the premium price secures a product that excels in function, longevity, and craftsmanship, representing a calculated choice for quality over disposability.

The Manufacturing Process: From Ancient Craft to Modern Metallurgy

The allure of a Damascus steel knife begins with its creation, a process steeped in both historical reverence and modern scientific precision. The original method, which produced what is now known as “Wootz” Damascus steel, involved a crucible technique perfected in regions of ancient India and the Middle East. Smiths would melt iron with specific carbon-rich plant matter in a sealed crucible, allowing it to cool very slowly over days. This process caused carbides to precipitate and segregate into microscopic bands within the steel ingot. When forged into a blade, these carbide structures created the distinct, watery patterns and provided a legendary combination of a hard, sharp edge and a tough, flexible blade body. This historical technique, the exact formula for which was lost to time, is the foundation upon which the Damascus legacy was built.

Today, the vast majority of what we call Damascus steel is technically “pattern-welded” steel, a modern revival and reinterpretation of the ancient aesthetic. This process involves layering two or more different types of steel alloys, which are then forge-welded together. A bladesmith will stack alternating plates of steel, heat the stack to a searing welding temperature in a forge, and then fuse the layers into a single, solid block, or billet, using the immense force of a hammer or a hydraulic press. This billet is then drawn out, cut, folded, and re-welded multiple times. Each fold doubles the number of layers, quickly building from a few initial plates to hundreds or even thousands of intertwined layers.

The selection of steel alloys is a critical, analytical aspect of modern Damascus production. Typically, a smith will combine a high-carbon steel, like 1095 or 1084, with a steel that contains a high level of nickel, such as 15N20. The high-carbon steel is chosen for its ability to achieve extreme hardness and excellent edge retention after heat treatment. The nickel-alloyed steel, in contrast, is tougher, more ductile, and importantly, resists acid. This differential property is the key to revealing the final pattern. Without this careful pairing of alloys, the subsequent etching process would not produce the desired visual contrast.

The final, dramatic step in crafting a modern Damascus blade is the acid etch. After the knife has been forged, ground to its final shape, and meticulously heat-treated to optimize its performance, it is submerged in an acid solution, most commonly ferric chloride. The acid attacks the high-carbon steel layers at a much faster rate than it does the nickel-rich layers. This differential etching process eats away material from the carbon steel, creating microscopic valleys, while leaving the nickel steel layers as raised peaks. This topographical difference is what creates the visual depth and the striking bright-and-dark contrast that is the hallmark of a pattern-welded Damascus knife, turning the internal structure of the steel into a visible work of art.

Understanding Damascus Patterns: The Art and Science of the Blade

The captivating patterns on a Damascus steel blade are not a superficial application but a direct visual representation of the smith’s skill and the blade’s internal structure. These patterns are intentionally and meticulously manipulated throughout the forging process, transforming a simple layered billet into a unique artistic statement. The final pattern reveals the history of how the steel was folded, twisted, and shaped, making each knife a one-of-a-kind piece. For the discerning buyer, understanding the common patterns provides deeper insight into the craftsmanship, complexity, and labor invested in the blade.

The most fundamental patterns are often referred to as “Random” or “Twist.” A random pattern emerges from the standard process of folding and forge-welding the billet, where the layers distort in a natural, organic, and unpredictable way. A twist pattern is created when the smith heats the rectangular billet and physically twists it along its axis, like wringing out a towel, before forging it flat again. This torsion shears the internal layers, creating a mesmerizing, star-like pattern at the center and a swirling, distorted grain along the flats of the blade. These foundational patterns are beautiful in their own right and are a testament to the core process of pattern-welding.

More advanced and deliberate patterns require additional steps of stock removal and manipulation. The “Ladder” pattern, for instance, is created after the layered billet is forged into a thick bar. The smith then grinds or cuts parallel grooves across the bar, removing material down through several layers. When the bar is then forged flat, the grooves disappear, but the points where they were cut force the layers to spread out, creating a pattern resembling the rungs of a ladder. Similarly, the “Raindrop” pattern is achieved by pressing a round-ended tool into the hot steel at regular intervals, creating divots that are then forged flat, resulting in a series of concentric circles across the blade’s surface.

At the highest echelon of the craft lies “Mosaic” Damascus. This incredibly complex technique involves constructing the pattern in the cross-section of the billet itself. Smiths may stack precisely cut bars of pre-patterned steel, or even use canisters filled with powdered metal and shaped steel pieces, to create an intricate image or geometric design. This entire construction is then forge-welded into a solid block. When this mosaic billet is forged and ground, the complex, picture-like pattern is revealed. This process requires an extraordinary level of planning, precision, and control, representing the pinnacle of the bladesmith’s art and commanding the highest prices.

True Damascus vs. Pattern-Welded Steel: A Critical Distinction

In any serious discussion of Damascus steel, it is crucial to make a professional distinction between historical “Wootz” steel and modern “pattern-welded” steel. The term “True Damascus” refers specifically to the former, a crucible-cast steel that originated in the Indian subcontinent around 300 B.C. Its defining characteristic was not layered construction, but a unique internal microstructure formed during a very slow cooling process. This resulted in the precipitation of iron carbides into distinct bands or patterns within a single ingot of steel. The legendary performance of these blades—their ability to hold a razor edge while remaining tough and resistant to shattering—was a direct result of this unique carbide segregation.

The methods for producing Wootz steel were a closely guarded secret, passed down through generations of smiths. The loss of this knowledge around the 18th century is a subject of historical and metallurgical debate, often attributed to a disruption in trade routes, the exhaustion of specific ore deposits containing key trace elements like vanadium and tungsten, and the breakdown of the oral traditions that preserved the craft. For centuries, smiths and scientists alike attempted to replicate it without success. Therefore, it is analytically accurate to state that no commercially available knives today are made from historically authentic Wootz Damascus steel.

What we universally refer to as Damascus steel in the contemporary market is pattern-welded steel. This is a technique of forge-welding different steel alloys together to create a layered composite. While inspired by the aesthetic of Wootz, the manufacturing process is fundamentally different. This is not a matter of deception, but of evolution in terminology. Pattern-welding is an ancient craft in its own right, used by Vikings and Japanese swordsmiths for centuries to create strong, resilient blades from the inconsistent materials available at the time. The modern practice has elevated this technique to an art form, focused on creating visually stunning patterns alongside high performance.

For the consumer, this distinction is paramount. Claims of selling “true,” “ancient,” or “lost” Damascus steel should be viewed with extreme skepticism. The value and quality of a modern Damascus knife should be judged on its own merits: the choice of steels, the cleanliness of the forge welds, the precision of the heat treatment, and the artistry of the pattern. While a high-quality pattern-welded blade offers an excellent blend of beauty and function, its performance characteristics arise from the lamination of modern, high-performance alloys, not from a rediscovered ancient secret. Understanding this allows a buyer to appreciate the knife for the masterpiece of modern craftsmanship that it is.

Proper Care and Maintenance for Lasting Performance

A Damascus steel knife is a significant investment in both performance and artistry, and its longevity is directly dependent on a strict regimen of care and maintenance. The primary enemy of most Damascus blades is corrosion. Because they are typically forged from high-carbon steels to achieve superior edge hardness, they are not stainless and will rust if neglected. The single most important rule is to hand wash and thoroughly dry the knife immediately after each use. Never place a Damascus knife in a dishwasher, as the harsh detergents, high heat, and prolonged exposure to moisture will not only initiate rust but can also damage the handle materials and dull the etched pattern.

The cleaning process should be gentle but effective. Use a soft sponge with mild dish soap and warm water. Avoid abrasive materials like steel wool or scouring pads, as these can scratch the surface of the blade and mar the delicate finish of the pattern. After washing, drying the knife with a soft cloth is not enough. It is crucial to ensure that every bit of moisture is removed, especially from the area where the blade meets the handle (the ricasso). A final wipe with a paper towel can help absorb any residual moisture, providing an extra layer of protection against the onset of rust.

For ongoing protection, especially for knives that are not used daily or are kept in humid climates, regular oiling is essential. Applying a thin coat of food-safe mineral oil or a specialized camellia oil to the blade creates a protective barrier that seals the steel from ambient moisture and oxygen. A few drops of oil spread evenly over the entire blade surface with a clean cloth is all that is needed. This simple step, performed after cleaning or before storage, is the most effective preventative measure you can take to preserve both the function and the beauty of your Damascus steel.

When it comes to sharpening, many owners express apprehension, fearing they will damage the pattern. This fear is largely unfounded. Since the Damascus pattern runs through the entire thickness of the steel, sharpening the edge on a whetstone or with a guided system will not erase it. The process is identical to sharpening any other high-quality knife. It is important to maintain a consistent angle to create a clean, sharp apex. The newly sharpened bevel may appear bright and shiny, temporarily obscuring the pattern at the very edge, but the pattern on the flats of the blade remains untouched. Over time and with use, a slight patina may even redevelop on the edge, blending it back into the overall aesthetic of the knife.

A Comprehensive Buying Guide to the Best Damascus Steel Knives

Damascus steel, with its mesmerizing, water-like patterns, evokes a legacy of legendary craftsmanship and unparalleled performance. Historically, the term referred to “wootz” steel, a crucible-cast steel from ancient India and the Near East, renowned for its ability to be forged into blades that were both incredibly sharp and resiliently tough. The secrets of its production were lost to time, but the allure remained. Today, the term “Damascus steel” primarily describes a modern marvel of metallurgy: pattern-welded steel. This technique involves forge-welding multiple layers of two or more different types of steel, which are then folded, twisted, and manipulated to create intricate patterns. When the final blade is acid-etched, the different steels react at varying rates, revealing the stunning layered design.

While the aesthetic appeal of a Damascus blade is undeniable, a discerning buyer must look beyond the surface beauty. The performance of a modern Damascus knife is not a product of mystique, but of deliberate engineering choices in steel composition, heat treatment, and blade geometry. A high-quality Damascus knife is a synthesis of art and science, offering a cutting experience that is as superior as its appearance is striking. This guide is designed to equip you with the analytical framework needed to navigate the market. We will deconstruct the six most critical factors to consider, moving beyond aesthetics to evaluate the practical, performance-driven elements that separate a functional art piece from a mere wall hanger. By understanding these key principles, you will be empowered to select a tool that meets the highest standards of both form and function.

1. Authenticity and Steel Composition (Core vs. Cladding)

The first and most fundamental consideration is the very nature of the steel itself. The market is unfortunately populated with counterfeit “Damascus” knives, which are typically low-quality, single-steel blades with a pattern laser-etched or acid-stamped onto the surface. These fakes offer zero performance benefits and the pattern will often wear off with use and sharpening. True pattern-welded Damascus is created by forge-welding layers of different steels, commonly a high-carbon steel like 1095 for hardness and a nickel-alloy steel like 15N20 for brightness and contrast. The pattern is therefore integral to the billet of steel and runs through the entire blade, revealed permanently through acid etching. When inspecting a knife, look for the pattern to extend across the spine and the cutting edge (if it’s not a laminated blade). Authentic Damascus has a depth and organic flow that a surface-level etching simply cannot replicate.

For high-performance kitchen cutlery, the most sophisticated construction is not a full Damascus billet but a laminated blade, often referred to as san-mai (three-layer). In this configuration, a central core of ultra-hard, high-performance mono-steel forms the actual cutting edge, and this core is then clad or jacketed in layers of softer, decorative Damascus steel. This approach provides the best of all worlds: the core, made from a premium steel like Japanese VG-10, AUS-10, or an exotic powder steel like SG2/R2, delivers exceptional edge retention and sharpness. The Damascus cladding, meanwhile, adds toughness, corrosion resistance, and the sought-after aesthetic. This construction is a hallmark of the best damascus steel knives for culinary applications, as it isolates the cutting performance in a specialized steel while using the pattern-welded steel for its beauty and protective qualities. Always investigate the core steel, as it is the true heart of the blade’s performance.

2. Hardness and Edge Retention (HRC Rating)

The hardness of a blade’s steel, measured on the Rockwell C scale (HRC), is a critical data point that directly correlates with its ability to hold a sharp edge. The heat treatment process, which involves controlled heating and cooling, determines the final hardness of the steel. In general, a higher HRC rating indicates a harder steel that will resist deformation and wear, thus maintaining its edge for a longer period of cutting. For instance, a blade with a 62 HRC will typically hold its edge significantly longer than one at 57 HRC under identical usage conditions. However, hardness is inversely related to toughness; an extremely hard blade can be more brittle and susceptible to chipping or fracturing if it strikes a hard object or is subjected to lateral stress. This trade-off is central to knife design and selection.

When evaluating a Damascus knife, the HRC rating provides a tangible metric for its intended performance. For general-purpose kitchen knives, a Rockwell hardness of 59-61 HRC is often considered the sweet spot, offering an excellent balance of long-lasting sharpness for slicing proteins and vegetables, while retaining enough toughness to withstand minor accidental impacts. Premium Japanese chef’s knives, particularly those with a powder steel core (like SG2/R2), can achieve hardness levels of 63 HRC and above, providing a surgical-grade edge for delicate, precise work. Conversely, a Damascus hunting or outdoor knife might be optimally hardened to a slightly lower range of 57-59 HRC. This prioritizes toughness and the ability to be easily re-sharpened in the field over the absolute longest edge retention, making the blade more resilient to the rigors of chopping and prying tasks.

3. Blade Geometry and Grind

While steel composition and hardness are foundational, the blade’s geometry—its cross-sectional shape and thickness—is arguably the most important factor in determining its actual cutting performance. A thick blade, regardless of its steel quality, will wedge through food rather than slice. Key geometric attributes to analyze include the thickness of the blade at the spine, the distal taper (the gradual thinning of the blade from the handle to the tip), and the primary grind. A significant distal taper enhances balance and allows for nimble tip work. The primary grind, which is the shape of the blade from the spine down to the cutting edge, dictates how efficiently the knife moves through material. Common grinds include the full flat grind, hollow grind, and convex grind, each with distinct performance characteristics.

For culinary tasks, a thin blade stock (typically 2-3mm at the spine) combined with a full flat grind is a superior combination. This geometry creates a very acute “V” shape that minimizes resistance and wedging, allowing the knife to glide effortlessly through ingredients. Some high-end Damascus knives feature an “S-grind,” which incorporates a subtle hollow on each side of the blade to create air pockets, reducing friction and preventing starchy foods like potatoes from sticking. For outdoor or survival knives, a more robust geometry is required. A “saber grind” (which begins partway down the blade) or a stout convex grind leaves more steel behind the edge, creating a much stronger and more durable blade that can withstand heavy use like batoning wood, at the cost of some pure slicing ability. Understanding these geometric principles allows a buyer to match the knife’s design to its intended purpose.

4. Handle Material and Ergonomics

A world-class blade is rendered ineffective without a comfortable, secure, and durable handle. The handle is the user’s primary interface with the tool, and its material and shape are critical to control, safety, and long-term comfort. Damascus knife handles are crafted from a wide array of materials. Traditional choices include natural woods like rosewood, ebony, and walnut, which offer a classic aesthetic and warm feel but may require periodic oiling and can be vulnerable to moisture and cracking. Modern synthetic composites like G-10 (a high-pressure fiberglass laminate), Micarta (made from canvas, linen, or paper in a thermosetting plastic), and carbon fiber offer superior durability. These materials are impervious to water, temperature changes, and impact, providing exceptional stability and grip, even when wet. A popular premium option is stabilized wood, which combines the natural beauty of wood burl with the resilience of a polymer resin impregnation.

Beyond the material, the ergonomic design of the handle is paramount. A poorly shaped handle will cause fatigue, hotspots, and a lack of control during extended use. Consider the primary grip you will use. For chefs who favor a “pinch grip,” the octagonal Japanese “Wa” handle offers superb control and allows for subtle adjustments in blade angle. For those who prefer a “hammer grip,” a contoured Western-style handle with a defined finger guard and palm swell may feel more secure. The size and shape of the handle should correspond to your hand size. A handle that is too small can cause cramping, while one that is too large can feel clumsy and unwieldy. The best Damascus steel knives feature thoughtfully designed handles that feel like a natural extension of the hand, facilitating precise and effortless cutting.

5. Tang Construction and Balance

The tang is the portion of the blade steel that extends into the handle, and its construction is a crucial indicator of a knife’s structural integrity and overall balance. The most robust and desirable construction is the “full tang,” where the steel is a single, solid piece that runs the entire length and profile of the handle. This design, visible as a metal spine between two handle “scales,” offers maximum strength and rigidity, making it the standard for high-quality Western chef’s knives and virtually all durable outdoor knives. The full tang ensures that the blade and handle are a cohesive unit, preventing any possibility of them separating under heavy stress. Knives can also feature partial tangs, such as a “stick” or “rat-tail” tang, where a narrower portion of steel extends into a handle that is then filled with epoxy. While common in traditional Japanese knives and perfectly sufficient for precision slicing, a full tang is generally superior for tasks requiring leverage or force.

The length and weight of the tang play a definitive role in the knife’s balance point. Balance is a critical, yet often overlooked, aspect of knife ergonomics that profoundly affects its handling and perceived weight. The balance point is the center of gravity. A “blade-forward” balance, where the point is located on the blade just in front of the handle, is often preferred by chefs as it allows the knife’s weight to assist in a natural chopping motion, making it feel more agile and responsive. A “handle-heavy” balance can provide a sense of security, while a “neutral” balance, right at the bolster or where the handle meets the blade, offers a versatile feel that adapts well to various cutting styles. When choosing a knife, holding it and identifying its balance point will tell you a great deal about how it will perform in your hand, a subtle but vital characteristic that separates a good knife from a great one.

6. Pattern, Aesthetics, and Finish

While performance should be primary, the signature aesthetic of Damascus steel is a significant part of its appeal and an indicator of craftsmanship. The specific pattern on the blade is determined by how the smith manipulates the layered billet during forging. A “Random” pattern is the most basic, while more complex designs like “Ladder” (achieved by cutting grooves into the billet and then flattening it), “Raindrop” (made by pressing round divots into the steel), and “Twist” or “Torsion” (created by twisting the billet) require additional skill and effort. The number of layers can range from under 100 to over 500. A higher layer count does not inherently improve performance but does result in a finer, more intricate, and more subtle pattern, showcasing a high level of technical mastery.

Finally, consider the overall fit and finish of the blade beyond just the Damascus pattern. The pattern’s visibility and contrast are brought out by acid etching; a deep, aggressive etch will create a dramatic, high-contrast look that can sometimes be felt, while a lighter etch offers a more subtle appearance. Look for unique finishing touches that add both beauty and function. A “Tsuchime” (hammered) finish on the upper portion of the blade, for example, creates small divots that act as air pockets to reduce food from sticking. Similarly, a “Kuro-uchi” (blacksmith’s) finish leaves the forge scale on the upper blade flats, offering a rustic look and a degree of corrosion resistance. The transition between these finishes and the polished, ground bevels should be clean and precise. These details, from the pattern’s complexity to the blade’s surface finish, are the final testament to the maker’s skill and attention to detail.

Frequently Asked Questions

What exactly is Damascus steel, and is modern Damascus the same as the ancient kind?

Modern Damascus steel, more accurately termed “pattern-welded steel,” is a composite material created by forge-welding two or more different types of steel alloys into a single billet. Typically, this involves layering a hard, high-carbon steel with a softer, more ductile steel. This billet is then heated, hammered, and repeatedly folded, a process which multiplies the number of layers. The distinct, wavy pattern for which the knives are famous is revealed only after the blade is ground to shape and submerged in an acid bath. The acid corrodes the different steel layers at slightly different rates, creating a topographical contrast that makes the pattern visible.

This modern technique is a re-invention and is functionally different from the ancient Damascus steel, often called “Wootz” steel, which originated in the Near East around 300 B.C. Wootz steel was a crucible steel, meaning it was made by melting iron with plant matter in a sealed vessel, creating a high-carbon steel with unique carbide impurities (like vanadium and molybdenum). These carbides would segregate into bands during the forging process, creating a surface pattern intrinsically. The specific recipe and technique for producing Wootz steel have been lost to history, so while modern pattern-welded steel emulates its legendary beauty, it is a different material made through a different process.

Are Damascus steel knives inherently better than other high-quality knives?

The performance of any knife—its ability to get sharp and stay sharp—is primarily determined by three factors: the quality of the cutting core steel, the precision of the heat treatment, and the geometry of the blade. The Damascus cladding on the sides of the blade is largely aesthetic. A well-made Damascus knife with a high-performance VG-10 or SG2 steel core will cut phenomenally well, but a monosteel (single steel) knife made from the exact same core steel, with an identical heat treatment and grind, will offer nearly indistinguishable cutting performance. The edge retention and sharpness are properties of that central core, not the layered steel supporting it.

However, the Damascus cladding does offer some functional benefits. The softer, often more stainless outer layers add toughness and resilience to the blade, helping to protect the harder, more brittle cutting core from chipping or lateral stress. This creates a blade that combines the extreme sharpness of a hard core with the durability of a softer spine. Ultimately, consumers choose Damascus knives for the unique synthesis of elite performance from the core steel and the unparalleled, one-of-a-kind artistry of the pattern-welded cladding. It isn’t automatically “better,” but it is a combination of top-tier function and high-end form.

Why are Damascus knives so expensive?

The high price of authentic Damascus steel knives is a direct result of the exceptionally skilled and labor-intensive manufacturing process. Creating a pattern-welded billet requires a master blacksmith to precisely layer and forge-weld different steel alloys together at extremely high temperatures. This billet is then folded and re-welded multiple times to achieve the desired layer count—a process that demands immense precision to avoid flaws or delamination. This artisanal method consumes far more time, fuel, and raw material than simply stamping or forging a blade from a single piece of steel (monosteel), which can be done with much more automation.

Beyond the complex forging process, the cost is also elevated by the premium materials used. Reputable Damascus knives are built around a high-performance central cutting core, such as expensive Japanese steels like VG-MAX, SG2, or Aogami Super. The cost of this premium core is then added to the cost of the steels used for the cladding. Finally, these knives are typically finished to a much higher standard, often featuring handcrafted handles made from exotic woods, Micarta, or G10, as well as meticulous hand-polishing and sharpening. This combination of skilled labor, premium materials, and artisanal finishing justifies their position as high-end products.

How do I properly care for and maintain a Damascus steel knife?

Proper maintenance is critical and non-negotiable for preserving the beauty and function of a Damascus knife. The cardinal rule is to always hand wash and immediately dry the knife. Never place it in a dishwasher. The combination of high-heat cycles, harsh detergents, and prolonged exposure to moisture will not only ruin the wooden handle but can also cause corrosion and permanently dull the etched Damascus pattern. After each use, use a soft sponge with mild dish soap and warm water to clean the blade, then dry it completely with a soft towel, paying attention to the area near the handle.

For long-term care and to prevent oxidation, especially if the core is high-carbon steel, it’s wise to apply a thin layer of food-grade mineral oil or Tsubaki (Camellia) oil to the blade after washing and drying. This creates a protective barrier against humidity. For storage, use a wooden knife block, a magnetic knife strip, or a traditional Japanese wooden sheath called a saya. These methods protect the delicate, sharp edge from being damaged in a drawer. Honing regularly with a ceramic rod will maintain the edge between sharpenings, and periodic sharpening on a whetstone is necessary to restore its peak performance.

Does the number of layers in Damascus steel affect the knife’s performance?

From a functional perspective, the number of layers in the Damascus cladding has a minimal to non-existent impact on the knife’s cutting performance. A blade with 33 layers and a blade with 101 layers will perform virtually identically in terms of sharpness and edge retention, provided they share the same core steel, heat treatment, and blade geometry. The actual cutting is done by the very fine edge of the hard inner core, which is a single, solid piece of steel. The layers are purely part of the cladding on the sides of the blade and do not extend to the cutting edge itself.

The layer count is almost entirely an aesthetic consideration that defines the appearance of the pattern. Fewer layers, such as 16 or 32, will produce a bold, wide, and wavy pattern. A higher layer count, such as 67 or more, creates a denser, more intricate, and often more subtle pattern that can resemble wood grain or flowing water. While some marketing may suggest more layers are better, there is no technical evidence to support this claim in terms of performance. Buyers should choose a layer count based on the visual pattern they find most appealing, rather than viewing it as a metric of quality.

What is the difference between pattern-welded Damascus and laser-etched patterns?

True, pattern-welded Damascus features a pattern that is an integral part of the steel’s structure. Because it is formed by physically forging together dozens or hundreds of layers, the pattern runs through the entire body of the steel cladding. You can often verify this by examining the spine of the knife, where the faint lines of the different layers should be visible. This structural pattern is permanent and cannot be worn off through normal use, cleaning, or even repeated sharpening. Over time, the visibility of the pattern might fade slightly, but it can be restored by re-etching the blade in acid.

In contrast, a laser-etched pattern is a purely superficial marking applied to the surface of a standard, single-piece (monosteel) blade to imitate the look of Damascus at a much lower cost. These patterns are often suspiciously perfect and uniform, lacking the organic, three-dimensional quality of real Damascus. The most definitive test is wear and tear; a laser-etched pattern will quickly fade or wear off with abrasive cleaning or, most notably, when the blade is sharpened, as grinding the metal away will remove the surface-level pattern and reveal the plain steel beneath. It offers zero performance benefit and is purely for decoration.

What should I look for in the core steel of a Damascus knife?

The core steel is the single most important factor determining a Damascus knife’s cutting performance, as it is the material that forms the actual edge. When buying, your primary focus should be on identifying this core material. For excellent all-around performance, look for knives with a core made of high-carbon, high-chromium Japanese stainless steels like VG-10 or VG-MAX. These steels are industry benchmarks, capable of reaching a Rockwell hardness (HRC) of 60-62, which provides outstanding edge retention while still being durable and relatively easy for a user to sharpen.

For those seeking the absolute highest tier of performance and willing to invest more, look for cores made from premium powder metallurgy steels. Steels like SG2 (also called R2) and ZDP-189 are created through a sophisticated process that results in an incredibly fine and consistent grain structure. This allows them to be hardened to an extreme degree (HRC 63-67), offering phenomenal, world-class edge retention that will stay “scary sharp” for significantly longer than other steels. While they can be more brittle and challenging to sharpen, they represent the pinnacle of modern blade steel technology. Always prioritize a well-documented, premium core steel over a flashy pattern with an unknown or inferior core.

Final Words

The selection of a Damascus steel knife transcends a mere appreciation for its distinctive aesthetic. A thorough evaluation reveals that the knife’s true performance—its edge retention, sharpness, and durability—is dictated not by the layered cladding but by the quality of the central core steel, such as VG-10 or SG2. Furthermore, critical factors including blade geometry, handle ergonomics, and the overall balance of the knife are paramount to its practical utility and user comfort. An informed purchase, therefore, requires a discerning analysis that looks beyond the superficial pattern to the fundamental components that define a high-quality cutting tool.

Our comprehensive reviews demonstrate a clear correlation between the grade of the core steel, the intricacy of the forge-welding process, and the knife’s resultant price point and performance tier. Consequently, prospective buyers seeking the best damascus steel knives must first define their primary use case and budget. For culinary professionals or serious enthusiasts prioritizing superior, long-term cutting performance, the evidence supports investing in a model with a premium powder steel core. Conversely, for home cooks or those prioritizing aesthetics on a more moderate budget, a knife featuring a reliable VG-10 core offers an excellent and justifiable balance of beauty, sharpness, and value.